Below, you will find a guide to the names and origins of the fictional characters of my trilogy for those reading Of Wind and Wolves and beyond. I’ve made a simple attempt to reconstruct the meanings of some of the following names, though many of these are incomplete. Though these remain disputed by scholars, I am not a linguist, so please take them for the informed guesses that they are.

Most of The Steppe Saga’s central characters are drawn from historical figures about which almost nothing is known. Developing credible characters from this dearth of information, for me, began with the one obvious piece of information available: their names.

Characters with a * next to their names are based on documented historical figures. Wherever possible, I have also provided artifacts which support this documentation.

ANAITI

Anaiti

undefiled, pure

· Western Iranian form Anāhiti, to the Greek form Anaïtis, to the more common form, Anāhitā.

Overseeing the bounty of the earth and the prosperity of the fields, crops, and domestic animals, etc, and sometimes called by her full descriptive name Aredvi Sura Anahita (watery, strong, pure), Anahita is an Indo-Iranian goddess of celestial and earthly waters, whom the Skythians may have simply called Api or Apia “The Waters.” Water temples, sanctuaries and shrines were common across ancient Persia, in contrast to the fire temples and hearths that were central to Indo-Iranian religious practice, and she was worshiped beside rivers and springs, often without an idol or image, but as the waters themselves.

Herodotus identifies Scythian Apia with Greek Gaia. Indeed, earth and water—in the form of rain, rivers, springs, lakes, etc.—are often inextricably linked in both creation and fertility myths and rites. Because the arid steppe is crossed by several important rivers, but can also stretch on for miles without water sources, the presence or absence of this resource and its life-giving properties would have been foremost in the minds of the nomads.

Rivers and other bodies were not only sources of sustenance and life in this world, but also provided natural boundaries, and came to represent important crossings to the Otherworld. Like the Rivers Styx and Lethe in Greek Mythology, many Indo-European traditions contain beliefs about crossings of sacred waters that must be accomplished to reach the spiritual realms of the dead.

Sometimes called the Persian Artemis, Anahita was also the planet Venus—the morning and evening star—and worshiped as a war goddess, granting victory in battle to the worthy, though this attribute appears to have originally belonged to a goddess called Ashi/Arti (the original Persian Artemis, in my view), which was eventually subsumed by Anahita’s growing popularity. She also may have invested kings with their sovereignty. There is some dispute over which divinity is shown in the coronation scenes depicted in the many artworks from across the steppe, as well as investiture scenes from Persia. Apia and Artimpasa have similar iconography, with both depicted having tendril limbs, though it has been argued that Apia is more strictly vegetal and Artimpasa anguipede. But that’s a discussion for another time. The immense popularity of Anahita in the south likely swallowed up other deities and their attributes and functions over time, making her an amalgam of several goddesses, and conferring on her all of their separate roles. Or, as many have supposed, perhaps all of these goddesses are simply manifestations of some primordial Great Goddess, whose roles, attributes, and influences were expansive. She also seems to have been closely associated with the god Mithra.

In the story, Anaiti is consecrated to Artimpasa, patron of the hamazon, but readers will also understand her name and connections to this water goddess, her namesake, who is at once a nurturer, a destroyer, and a mysterious gatekeeper to an unseen world.

ARIAPAITHI*

Ariapeíthes - Ἀριαπείθης (Herodotus, Book IV, 78)

Honorable Lord

· aria - trusty, honorable, worthy

· paiti - lord, ruler

King Ariapeithes is mentioned only briefly by Herodotus, but we know quite a bit about him through the few details we are given. He has three sons, all by different mothers: One Istrian, from a precariously situated Hellenic colony near the mouth of the Danube with a complicated relationship to both Scythia and Thrace; one Thracian, daughter—then sister—to the powerful rulers of the new Odrysian kingdom; and one Scythian, a queen named Opoea. His sons grow to be equally complex figures. The exact location of his tomb is unknown.

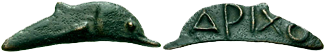

ARIC*

Oricus - ‘Οριkoς (Herodotus, Book IV, 78)

the one who upholds right order, justice

Herodotus was kind enough to provide us the names of Scythian King Ariapeithes and his three sons, the youngest of whom was called “Oricus”—at least this was the Greek transliteration of his name. Based upon some other evidence, such as coins from the same period, a host of other figures with similar sounding names, and a later legend surrounding the exploits and fates of three Iranian brothers, the youngest of whom is called “Ērič,” it is fair to assume the historical man referred to in The Histories was called something like “Aric.”

The name likely derives from both the Proto-Indo-European root reg- ‘to go straight, straighten, stretch out’ and the related Indo-Iranian/ Vedic rtá/Avestan arta ‘right order, truth’ hence ‘the one who upholds right order, justice’ which has cognates in other Indo-European languages from which raj, rig, rik, and rex are also derived.

Some have conjectured that the term “rig/rex” always meant “king/ruler;” however, based on the original historical application of the term, it seems that it referred instead to individuals tasked with a protective function. This may spill over into political leadership roles, but rarely vice versa. PIE ‘reg-’ seems to suggest movement in a straight line, stretching out, straightening, ordering, as do most of the words derived from it. “Law” and “order” were supplied by two different entities in the Indo-European consciousness, and in these societies, the “rig/rik/rex” provided the order—or set things straight.

The rig/ric/rek/rex element appears in the names of war leaders across several European language families: Genseric, Alaric, Ermanaric, Vercingetorix, Theodoric, Boiorix, Orgetorix, Dumnorix, Cingetorix, Ascaric, etc. So, our fictional war chief Aric is in good company.

OKTAMASAD*

Octamasades/Oktamasádes - Ὀκταμασάδες (Herodotus, Book IV, 80)

speaker/friend of wisdom?

· okta - invoked/addressed

· ucta/uxta - said/proclaimed

· haxā - friend

· mazda - wisdom

The historical Oktamasades, whose mother was Thracian, was the grandson of the founder of the Odrysae kingdom, King Teres of Thrace, and nephew of King Sitalkes and Sparatocus. His mother’s name is not recorded, though her son manages to live an eventful, if somewhat troubled, life.

Several scholars have suggested that the famous Solokha kurgan, which holds two impressive burials from the period, might be the resting place of both Octamasades and his brother Oricus, according at least to A. Yu. Alekseyev1 That the two might have shared such a grand burial mound is not only unusual, but of course invites intriguing questions about their fraternal relations in life.

A Ukranian folktale called “Christmas Eve” and an opera of the same name by Rimsky-Korsakov featured a witch named Solokha, and one wonders why this particular name was given to this particular barrow…

SKYLES*

Skyles - Σκύλης (Herodotus, Book IV, 78)

named for Scythian progenitor and culture hero Skythes?

· dialect shift: *skuδa-tæ > *skula-tæ ; Skythes > Skyles ; δ > l

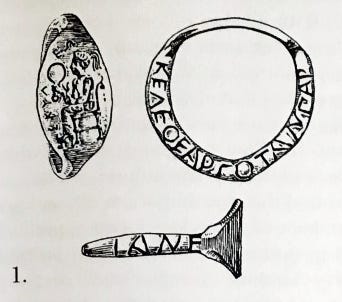

The signet ring (above) contains and inscription on the face:

ΣΚΥΛΕΩ

SKYLEO: “I belong to Skyles.” The seated figure of a woman holding a mirror is likely an image of the enthroned goddess, holding a mirror and leaf or flower (and wearing elf shoes!), who bestows sovereignty upon the ruler. Another inscription, likely older, encircles the band of the ring reading:

ΚΕΛΕΟΕΑΡΓΟΤΑΝΠΑΡ—IΑΝΕ

The meaning of this inscription has been disputed by scholars, none of which are particularly satisfying. I offer my own interpretation in Book II, The Gifts of Heaven. If you read Greek, please offer yours! I’d love to hear some more ideas.

The ring was recovered six miles south of Istria, the hometown of Skyles’ Hellenic mother, among coins dated to around 450 BCE near the site where Skyles’ death was reported to have occurred, making it likely that it belonged to Skyles himself, and that he lost it during his final hours, detailed in Book III, Peace Weaver, or that it was given to an acquaintance in the nearby city.

The historical Skyles—or what we know of him from Herodotus and a handful of clues—is a complex figure and the reason I wanted to explore this story in the first place.

ANTISTHENES

Antisthenes - Ἀντισθένης

In the story, Antisthenes is a Hellene living among the Skythians who plays a central role in the story. His own story is complicated, and he is a somewhat inscrutable figure both to the reader and to his fellow characters, so I thought it only fitting to tie him to an artifact with an equally enigmatic history. His name comes from a silver kylix found in the Solokha mound which bears two separate and nearly illegible inscriptions:

ΕΡΜΩΝ ΑΝΤΙΣΘΕΝΗΣI ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡIΑ | ΛΥΚΟ

ERMON ANTISTHENES ELEUTHERIA | LYKO

A proposed interpretation:

[From] ERMON [to] ANTISTHENES [in celebration of] ELEUTHERIA | LYKO [Wolf]

Yes, the kylix also mentions a third character, Lyko, who readers will meet in Book III, Peace Weaver.

A Greek philosopher by the name of Antisthenes (446 – c. 366 BC) would later be credited as the founder of the Cynic school, which some say greatly influenced the Stoics. Had he truly lived, Antisthenes of Scythia might have been an inspiration to them all.

Eluetheria may, as some suggest, be a reference to the popular festival of the same name. Or perhaps, it had the more literal meaning of “freedom, liberty.” It is also one of the many epithets of Artemis.

ERMAN

Ermon - Ερμων

right conduct, hospitality, social contract, healing

· Aryaman - Indo-Iranian concept and divinity

Associated with social and marital bonds, as well as healing, Ermon/Erman is derived from Aryaman or Airyaman (of the triad Mitra-Varuna-Aryaman). When used as a common noun, aryaman- means ‘comrade’ and NPer irman means ‘guest.’ It has cognates in other European languages such as Irish Eremon, Gothic Ermanaric; Old Norse Iormungandr, Old Saxon irminman, Irminsul, etc.

The Ermon whose name was inscribed on the silver kylix found in the Solokha kurgan (see details above under Antisthenes) was most certainly not an enaree/anarei (i.e., a diviner/shaman who practices ritual transvestism), but possibly Greek or a Hellenized Scythian. Some have speculated that his name was a form of Hermes (Hermon), which I would suggests has its distant roots in the same place as all of these others. In their own way, they all suit the fictional character of Erman, the multifaceted seer and adviser to the king.

OPOEA*

Opoea (Herodotus, Book IV, 78)

Divine Mare?

· aupavahaya - divine mare, royal mare

Little is known about Queen Opoea except that she was the Scythian mother of the youngest prince Oricus, and that when the king died, she married his successor. I won’t say more than this for now…

The prospect that her name might signify divine or royal mare is interesting to me, as it would place her in a class with figures like Epona, Macha, Rhiannon, as well as Demeter Erynis and others, and recalls how rituals like the Ashvamedha were designed to confer sovereignty through the agency of a divine figure, often in the form of a mare. Royal women, in particular, served a crucial spiritual role within the society in acting out the roles of the goddesses on earth, conferring fertility and prosperity on all under their domain. Association with horses seems to have been a vital element in conferring power and legitimacy in this role.

ARIANTA*

Ariantas - Ἀριάντας (Herodotus, Book IV, 81)

Honorable Warrior?

· aria - trusty, honorable, worthy

· ta - warrior

Herodotus mentions the Bastarnae and Ariantas in conjunction with a brackish sacred spring called Exampaeus, or Holy Ways, the taking of an unprecedented census, and a massive cauldron, which readers will learn more about in Book III, Peace Weaver. The Bastarnae are a mixed tribe of likely Germanic and Scythian people farming in the forest-steppe region northwest of the nomadic Scythians.

SPARGAPAITHI*

Spargapeíthes- Σπαργαπειθης (Herodotus, Book IV, 78)

Lord of Battle Din/Divine Ruler?

· spargga - noise, twang, din (as of battle)

· svarga - heavenly

· paiti - lord

Spargapaithi’s key role in the story is related by Herodotus, which I won’t mention now as it would be a major plot spoiler. Little else is known about the historical man. While this king of the Agathyrsi tribes remains offstage for the duration of the first volume of The Steppe Saga, his spectre looms large over much of the novel. In the story, his reputation for cruelty and his acts of depredation are known far and wide, and the threat he poses to both the Skythians and Anaiti’s people, the Bastarnae, are always present, overshadowing their choices.

He makes his presence keenly felt in Book II, The Gifts of Heaven, and makes his boldest appearance in Book III, Peace Weaver.

TYMNA*

Tymnes/Thymnes (Herodotus, Book IV, 76)

strong?

· ttumna - strong, stout

Tymnes is mentioned by Herodotus as the “deputy” of Ariapeithes, or performing some other role in his government. Herodotus claims to have spoken directly to him, and he may have indeed been one of the sources who provided information to Herodotus in writing Histories.

In The Steppe Saga, and perhaps history, he has a front row seat to some of the action, the king’s ear on sensitive matters of state, and a hand in shaping the future of Skythia, for better or worse.

I hope this brief guide has helped familiarize readers not only with the central characters who populate The Steppe Saga trilogy, but with the strange and wonderful world they are drawn from.

Often authors choose character names because they highlight or hint at an aspect of that character’s nature, bear some deeper symbolism, or imply something about the history or fate of the character. However, when writing historical fiction, authors are usually writing about real people, or at least people whose names we don’t always have the luxury of choosing. While we may work to discover who these individuals were, or at least create some reasonable impression of who they might have been, we’re not at liberty to choose their names—not all of them.

Yet, names can still play an interesting role in characterization. One of the wonderful things about the past is that people were often given names relevant and meaningful to the individual. Sometimes these were hyperbolic or aspirational, but they referenced something about the person’s personality, occupation, family, or deeds in life. They are a vivid depiction of how an individual was perceived—or hoped to be—by his or her society. In the absence of so much other testimony, names can be an interesting witness to interrogate.

Historical artifacts are another way to connect to a character. As a reader of historical fiction, I want to learn vicariously about the world of the past through a story’s characters. As someone with an interest in archaeology, I want to be able to connect characters with an artifact, which can ground them with something tangible: an object they might have actually used, looked at, touched, loved—something from their world that would have been familiar. Artifacts, artworks, inscriptions, verses, and myths invite us into the traditions of the past, and can serve to humanize the people who created them when they can no longer explain their culture and beliefs to us. We are remiss if we don’t try to read them honestly and interpret them sympathetically, as we hope those in the future will interpret our creations and possessions when it’s their turn to speak for us. Fiction may be one of the last, best places to attempt this.

Every artifact has its own story to tell, and its own history. These stories become intertwined with our stories in fascinating ways, in which we leave our impression on objects, and they leave their impressions on us. Some of these marks are still discernible after thousands of years. Familiar images, favorite objects, and artworks can give an insight into the hearts and minds of people in ways history books never can. Just as they provide insights to the archaeologist, anthropologist, and historian, they have been invaluable guides to me in my writing process.

If you have questions about any of the characters, their background, or development, please don’t hesitate to ask!

“Scythian Kings and ‘Royal’ Burial Mounds of the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC,” Scythians and Greeks: Cultural Interactions in Scythia, Athens and the Early Roman Empire, 2005

Fantastic research and history lesson. I'm quite surprised and interested by how consistent world mythology is. While the names and faces change, the underlying mythos is quite similar the world over.

And then there is the question of how much fiction is actually fictionalised ancestral memory. I once set an entire fantasy novel in a desert kingdom around a city I called Samarkand that was rich from trade. and it was moorish in nature. Only to discover that a moorish city called Samarkand exists on the silk road. I had never had any interest in Eastern culture before then so it's unlikely I picked this up in earlier years. Weird. This happens to me so often now that after I write something I go and research the details to see if it's popping up in history somewhere and if so I tweak things a bit to make it consistent with that historical context. But I am in no way a historian, more an enthusiast for various time periods.

Incredible. I'm humbled by your character research. I've always been afraid of historical fiction because I know it requires this herculean research regimen. Regarding character names, Tolkien was one of the best, I think. His names were always so fitting and filled with personal history for the character. I often do times writing about my characters, sometimes around their favorite or most cherished objects, etc., just to help me discover them. Niece piece. Thanks!