Ok, this is a long one. Too long for some email. If you’re interested, it can be viewed in its entirety at jmelliott.substack.com.

When a shepherd’s cow stepped on a sword buried somewhere on the steppe in the early 400’s CE, he immediately dug it up and rushed it to his leader. It was clearly a sign. For, it was no ordinary sword, but the Sword of God, designating the chief, Attila, ruler of the world.

At least, that’s the story Attila told. And maybe he believed it. But, why should a cowherd or Atilla assume that some old sword buried in a pasture and stomped on by a cow was anything special, much less the Sword of God? What made this random sword particularly portentous?

As it turns out, there was a long tradition of divine swords on the steppe preceding Attila’s arrival. The Scythians held such swords sacred, and built oddly insubstantial sanctuaries to house and honor them across their domain. There was supposedly a sword-temple in every tribe’s district and, each year, extravagant sacrifices would be made to its deity. The Sarmatians, cultural cousins to the Scythians, who had by now mostly displaced them, still continued the tradition of worshiping these swords stuck in the ground almost a thousand years later. So, literally stumbling on one of these relics, Attila’s cowherd would not have seen it as a random mislaid sword. He would have understood that it was extraordinary.

The Eastern Roman historian Jordanes cames to the same conclusion when he told the story of Attila and the discovery of his iconic blade in his history of the Goths:

§ 183 And though his temper was such that he always had great self-confidence, yet his assurance was increased by finding the sword of Mars, always esteemed sacred among the kings of the Scythians. The historian Priscus says it was discovered under the following circumstances: "When a certain shepherd beheld one heifer of his flock limping and could find no cause for this wound, he anxiously followed the trail of blood and at length came to a sword it had unwittingly trampled while nibbling the grass. He dug it up and took it straight to Attila. He rejoiced at this gift and, being ambitious, thought he had been appointed ruler of the whole world, and that through the sword of Mars supremacy in all wars was assured to him."

Who is this sword god?

Herodotus mentions numerous Scythian deities whom he interprets as corresponding to Greek gods, carefully transliterating their Scythian names alongside their assumed Greek counterparts:

Tabiti (Ταβιτί) – Hestia

Papaios (Παπαῖος) – Zeus

Api (Ἀπί) – Gaia

Oitosyros/Goitosyros (Οἰτόσυρος) – Apollo

Argimpasa/Artimpasa (Ἀργίμπασα) – Aphrodite Urania

Thagimasidas (Θαγιμασάδας) – Poseidon

Scythian Ares (Greek: Ἄρης) – Ares (no uniquely Scythian name is given for this god).

The only god for which he provides no apparent Scythian name is one he refers to as “Ares,” linking him to the Greek war god. Most scholars have simply assumed that there was a Scythian name attached to this Ares which Herodotus and history neglected to record or his informants omitted. Perhaps the name of the deity was taboo, or it just never came up in conversation. We’ll come back to this a little later.

The sanctuaries of Ares

More importantly, Herodotus describes what the sanctuary of Scythian Ares was like and how it was used:

§ 4.62 To the others of the gods they sacrifice thus and these kinds of beasts, but to Ares as follows: — In each district of the several governments they have a sanctuary of Ares set up in this way: — bundles of brushwood are heaped up for about three furlongs in length and in breadth, but less in height; and on the top of this there is a level square made, and three of the sides rise sheer but by the remaining one side the pile may be ascended. Every year they pile on a hundred and fifty waggon-loads of brushwood, for it is constantly settling down by reason of the weather. Upon this pile of which I speak each people has an ancient iron sword set up, and this is the sacred symbol of Ares. To this sword they bring yearly offerings of cattle and of horses; and they have the following sacrifice in addition, beyond what they make to the other gods, that is to say, of all the enemies whom they take captive in war they sacrifice one man in every hundred, not in the same manner as they sacrifice cattle, but in a different manner: for they first pour wine over their heads, and after that they cut the throats of the men, so that the blood runs into a bowl; and then they carry this up to the top of the pile of brushwood and pour the blood over the sword. This, I say, they carry up; and meanwhile below by the side of the temple they are doing thus: — they cut off all the right arms of the slaughtered men with the hands and throw them up into the air, and then when they have finished offering the other victims, they go away; and the arm lies wheresoever it has chanced to fall, and the corpse apart from it.

As noted above, the Sarmatians also engaged in much the same lifestyle, including its warfare, worship, and sacrifice, as attested by Ammianus Marcellinus:

§ 31.2.21-23 Moreover, almost all the Halani [Alans, a Sarmatian tribe] are tall and handsome, their hair inclines to blond, by the ferocity of their glance they inspire dread, subdued though it is. They are light and active in the use of arms. In all respects they are somewhat like the Huns, but in their manner of life and their habits they are less savage. In their plundering and hunting expeditions they roam here and there as far as the Maeotic Sea and the Cimmerian Bosporus, and also to Armenia and Media.

Just as quiet and peaceful men find pleasure in rest, so the Halani delight in danger and warfare. There the man is judged happy who has sacrificed his life in battle, while those who grow old and depart from the world by a natural death they assail with bitter reproaches, as degenerate and cowardly; and there is nothing in which they take more pride than in killing any man whatever: as glorious spoils of the slain they tear off their heads, then strip off their skins and hang them upon their war-horses as trappings.

No temple or sacred place is to be seen in their country, not even a hut thatched with straw can be discerned anywhere, but after the manner of barbarians a naked sword is fixed in the ground and they reverently worship it as their god of war, the presiding deity of those lands over which they range.

Brush with fate

It's unclear why “brushwood” is the chosen building material in the Scythian example, or whether this is maybe a mistranslation or misunderstanding on the part of Herodotus and his interpreters. Building materials on the steppe were limited, though the nearby forest-steppe region would have been able to supply ample brushwood for those who could transport it. But for tribes without the resources, trucking brush by the wagonload from abroad was probably not an option. Herodotus’s informant does seem to have been connected to the “Royal Scythians,” and therefore may have been describing practices possible for the well-resourced, but simply unrealistic for the average steppe tribe.

But it still doesn’t explain why something so insubstantial would be a preferred building material for anyone when kurgans (burial mounds) were constructed like earthen pyramids from bricks of sod, which was available everywhere on the steppe. Further east, kurgans were also constructed like cairns, by piling stones atop timber “log-cabin” style chambers. So, other materials and methods were clearly available, which makes this description stand out as especially bizarre. It would be fun to think it was just a practical solution to all the crap left at the end of seasonal yard cleanup. In fact, I’m tempted to shove a sword in the ever-expanding brush pile at the back of the farm here and declare it a sacred monument.

Herodotus himself mentions that the temples “settle” due to the weather and need to be replenished yearly. In other words, they compost and decompose. Maybe the rotting signifies death. Or perhaps they become fertile and sprout new growth. Maybe both. I’ve tended to think about them in the way I think about the tradition of bringing greenery indoors for the Christmas season. Yes, eventually the cut boughs and trees have to be tossed, but they’re symbolic of something while they last. Either way, constructing an entire sanctuary from such materials would be a powerful statement, whether we ever know quite what it meant.

And, maybe they weren’t composed entirely of brushwood, but overlaid, dressed, or decorated in some kind of sacred plant or greenery as part of the ceremony, and gathering and replenishing the materials was part of the observance.

There is the possibility that, as sacred structures, there was a ritual element to the construction or a symbolic element to the material. For example, we know that some Hindu and Buddhist rituals called for the laying of kusha grass as a seat for both priests and gods. According to hindupedia.com (no hyperlink because the site was not https secure):

Barhis literally means 'that which is plucked up', 'sacrificial grass'. Vedic sacrifices involve a lot of details to be looked into while organizing their performance. One such is the spreading of the kuśa grass in the sacrificial shed and more so on the vedi (sacrificial platform) upon which the sacrificial vessels and oblations are kept.

The seat of the performers and the place where the gods invited to receive the offerings are expected to be seated, are also situated here. This place thus covered with the kuśa grass, is called ‘barhis’.

And Zoroastrian rites also include bundles of twigs, known by a related word, barsom:

BARSOM (Av. barəsman), sacred twigs that form an important part of the Zoroastrian liturgical apparatus. The word barsom is the Middle Persian form of the Avestan barəsman, which is derived from the root barəz, Sanskrit bṛh “to grow high.” The barəsman twigs were twigs of the haoma plant or the pomegranate used in certain ceremonies. They are first laid out and then tied up in bundles. The number varies according to the ceremony to be performed.

The object of holding the barsom and repeating prayers is to praise the Creator for the support accorded by nature and for the gift of the produce of the earth, which supplies the means of existence to the human and the animal world. The object of selecting the barsom from the twigs of a tree is to take it as a representative of the whole vegetable kingdom, for which benedictions and thanks to the Creator are offered, and there is further proof to show that the performance of the barsom ritual is intended to express gratitude to the Creator for His boundless gifts. (from Encyclopædia Iranica)

A sacrificial platform; a “seat” prepared for the gods with sacred vegetation; and the manipulation by priests of holy bundles of sticks symbolizing the produce of the earth. While it may be difficult or impossible to unpack all of these elements, a clearer picture of the ancient Indo-Iranian ritual landscape comes into focus, and it becomes far more plausible that some or all of these elements were not only present in the Scythian sword cult, but that they were either deployed in a unique and possibly archaic fashion by the Scythians, or were incompletely conveyed during the game of cultural telephone Herodotus played with his regional interpreters. While we’re playing telephone, if you squint a little with your ears, maybe barəz could even sound a little like Ares…?

The archaeology

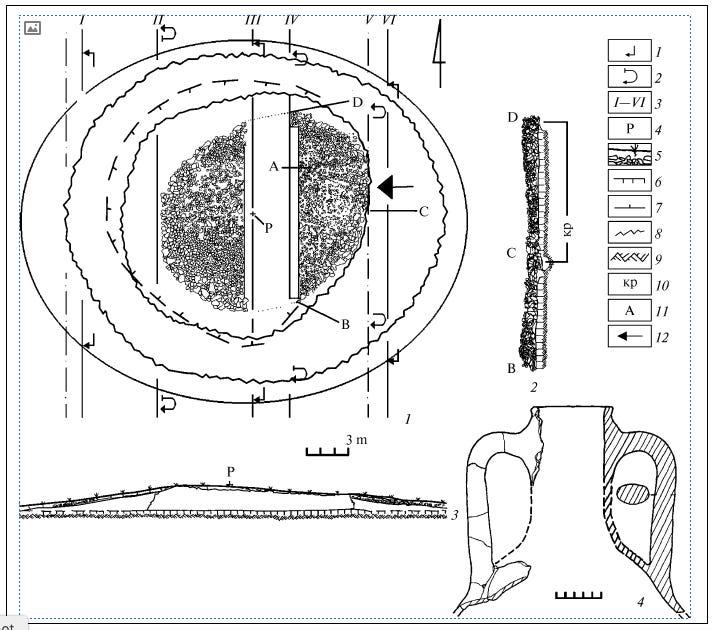

In a site near the Ukrainian village of Kremenivka (formerly a Greek settlement of Cherdakli) along the ridge of the watershed of the Kalchyk and Kalets Rivers (right tributaries of the Kalka River) lies a necropolis of some 25 kurgans.

Two mounds sit conspicuously apart from the main body of the cemetery, which are otherwise all aligned along the same axis on the ridge.

“Kurgan 5” contains no traces of burials and is not round like most burial mounds, but oval, being 32 x 26 m, and approximately 1.75 m high. It is also built from granite stones, surrounded by a bank, and has a relatively flat summit, sloping slightly to the east. Under the bank of this eastern slope, the handle of a red clay amphora and other fragments were found.

Close to this eastern slope sits “Kurgan 7.” Also oval-shaped, it is about 30 m long and .7 m high, though it has been heavily damaged by plowing. This structure has a unique feature in that its south-western side is open, forming a hollow or horseshoe shape. Inside, along the northern wall of this hollow, numerous artifacts were discovered, including fragments of amphorae, a cauldron, and animal bones. Additional finds from around the structure included a mirror, fragments of amphorae and black-slip vessels, more animal bones including sheep, goats, cattle, and horse, a bridle frontlet, a whetstone, and an iron buckle. On the stones above the hollow, a piece of bronze plaque and bowls were found.

According to archaeologists Gershkovych and Romashko:

‘Kurgan 7’ seems to have been the place where sacrificed persons were dismembered and animals were slaughtered: amphorae found there contained wine needed for ‘pouring’; it was there that animal bones were discovered, while the black-slip bowl and other similar vessels could have served for keeping blood and for carrying it up on the top for ‘pouring over the sword’.

Without belaboring the dating of the artifacts too much, they point to use of the site probably during the early to mid 4th c. BCE.

Though it is not made of brushwood, this certainly sounds like a sanctuary or temple, with all the trappings of sacrifices, rituals, and feasting. The Scythians supposedly didn’t make temples to any god but “Ares.” So, can we assume that this platform is an example of one such temple?

What’s more interesting is that they represent two structures seemingly comprising a single cult complex, with features that reappear in different periods and different territories. Though the conditions of this site would not have been favorable to the preservation of human bones or iron swords, this is not true of other, similar sites.

Other examples:

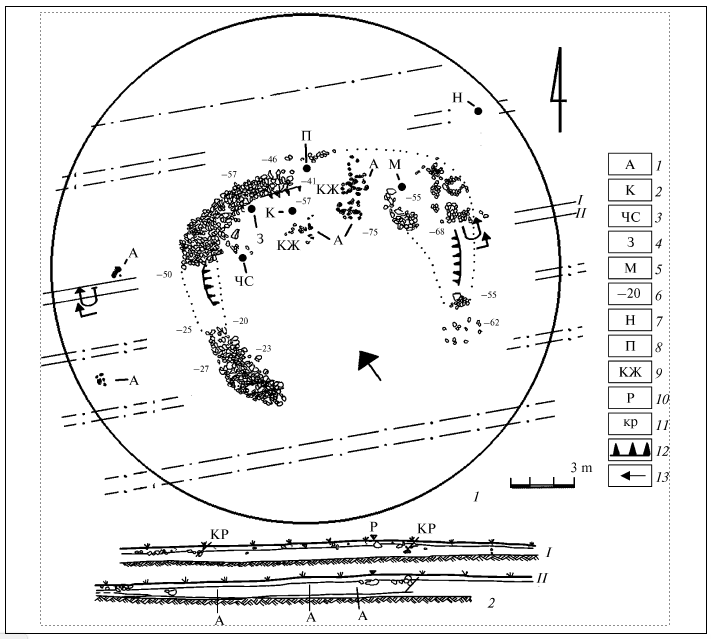

The archaeologists believe there are grounds to suggest that “Kurgan 7,” near the village of Balky, Vasylivka district, Zaporizzhia region is also a sacrificial altar. At 2.7 m high, with a diameter of 42 m, a 5th c. BCE iron sword—possibly already an antique while in use—was found buried on the bank. Opposite the bank, on the east side, was a trough-shaped depression in which ceremonial objects, like a granite quern, and animal bones were found.

Another suspected altar is located between the villages of Semenivka and Starokozache, Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi district, Odessa region. Here, a small “kurgan” among the burial ground stood out for having numerous deposits of various styles of amphorae fragments, fragments of sockets, spear finials, pieces of horse harness, including a bronze bridle frontlet, and a goblet made of cast glass filled with iron trilobate arrowheads and bronze brackets. Most tellingly, there were remains of an iron acinace (akinaka, a Scythian-style short sword) or dagger, erected with its hilt buried in the earth.

In Perevalsk, Luhansk region, locals found a bronze cauldron with vertical handles, characteristic of sacrificial vessels, on the slope of one of the kurgans. It contained several golden plaques in the famous Scythian animal style, suggesting a ritual purpose for the site.

Then there are the Ulskiy and Uliap “kurgans” in the Kuban region which contain approximately 1 m high platforms with an entrance ramp at one side. According to the paper, they are “made from ground, chips and brushwood” which is a little unclear, but I assume means woodchips and brush.

The Ulskiy mound contains traces not only of horse, ox, ram, and donkey sacrifices, but also humans. Dismembered human skeletons were also found at the Uliap site, including a skeleton missing a right hand. These bones were found at the opposite end of the platform near an iron sword. They provide frustratingly little information about these last excavations.

This verification of Herodotus again speaks to a widespread and long-lasting tradition of worship on the steppe which, though regionally varied, retained the essential character of a sacrificial sword cult requiring an altar or sanctuary. The tradition first described by Herodotus in the 5th c. BCE retained its essential elements and character, but either developed a more archaeologically enduring form, or became more widely spread as time progressed, reaching its height at the end of the 4th and early 3rd c. BCE.

Is Greek Ares adopted?

They worship no gods but Ares, Dionysus, and Artemis.

—Herodotus, on the Thracians

“Ares” was apparently a popular god in Thrace as well, and some claimed the Greek Ares even originated in Thrace.

Most ancient societies around the world had a war god, and the Greeks were no different. In fact, they had more than one. However, once they began to fancy themselves enlightened and rather above such things, they decided their Ares, one of their more brutish deities, was gauche and vulgar, and that such a barbaric god could not have been the product of their noble pantheon, but was an immigrant from barbarian lands. The embarrassed Greeks wanted nothing to do with Ares, so they pawned him off on the uncouth Thracians. In case you thought the desire to disavow one’s cultural heritage and revise unflattering history was an annoying quirk of the modern era, rest assured, the ancients were doing it long before us. Blaming others for one’s imagined shortcomings—moral or otherwise—is a time-honored tradition.

Was Ares a foreign import? Probably not. An early Mycenaean Greek form of the word/name, a-re, is attested in Linear B script from the most ancient phase of Greek language. However, the distinct roles fulfilled by most of the Indo-European gods of fire, water, sky, earth, storm, etc. are almost uniformly comparable across cultures. Even their names are often similar. It would not be surprising for many “Ares” to exist across the IE spectrum, even if their names and characters diverge somewhat by region. In fact, it would be surprising if they didn’t. But, what would their common element be?

Greek Ares wasn’t the god of every aspect of war. He presided over the messy parts, closest to the ground and deepest in the gut—the chaos, din, and frenzy of battle. What tends to link war gods is that they generally start their careers as storm gods—governing the storms within and without. They have a complex role to play in providing for the fertility and prosperity of the land. Without some storms, especially in spring, nothing grows. Too many storms or too violent, what grows is destroyed. There is a message in there about the role of the tempestuous warrior and his raiding and warfare—a delicate balance between risk, reward, and ruin. So these moody war gods held power over every aspect of life and death for the people, and it was easy for them to fall in and out of favor as circumstances dictated—as did the warriors they came to be patrons of. With more to lose, perhaps people lost their tolerance for turbulent forces, even those that raged on their behalf.

What’s in a name?

Lucian of Samosota wrote in his Toxaris that the Scythians swore oaths of friendship by “Wind and Sword” without providing names for either. But through the Scythian character of Toxaris, he described the nature of both gods:

Tox. What can you mean? Wind and Scimetar not Gods? Are you now to learn that life and death are the highest considerations among mankind? When we swear by Wind and Scimetar, we do so because Wind is the cause of life and Scimetar of death.

In this dualism, Sword is not the face of the war god, but of Death itself—counterpart to Life. At first glance, these two understandings may seem irreconcilable, but we’ll get to that soon.

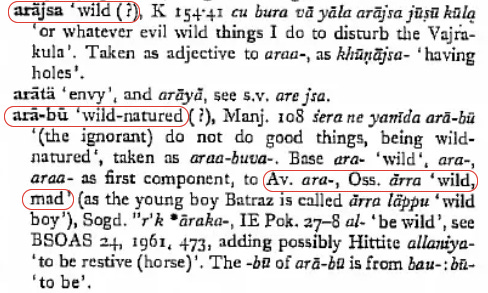

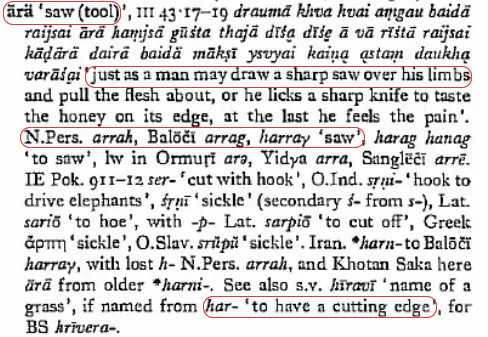

I’ve wondered if perhaps the Scythian name of this Sword deity, or the epithet by which he was most commonly known sounded near enough to “Ares” to the Greek-speaking ear that there was no need to record a Scythian alternative. If so, what might this name, in an Iranian language, have been? In other words—and this is purely speculation—maybe Scythian Ares simply had a name that sounded enough like Greek Ares that it didn’t warrant its own transliteration?

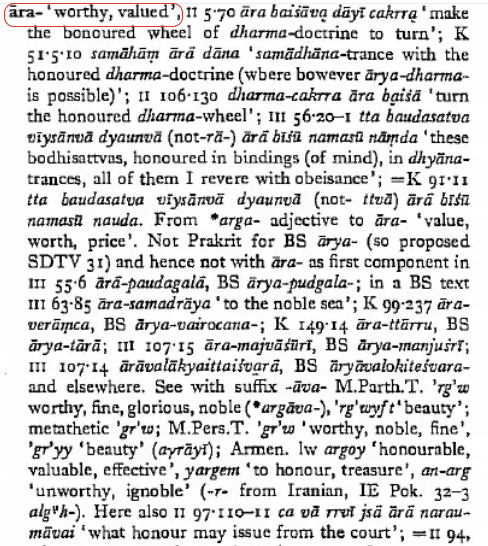

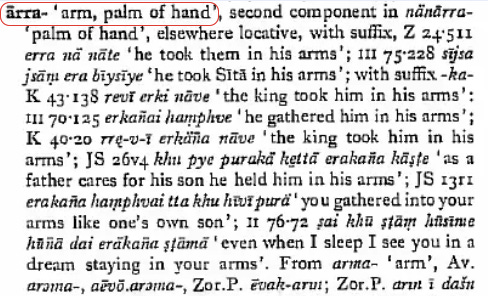

Now, bear with me a moment here. I’m obviously not a linguist, and this isn’t a scholarly monograph. But part of why I write is the opportunity to think aloud. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary Ares, from greek arē, means "bane, ruin." Several arē adjacent words exist in old Indo-Iranian languages, though their meanings vary. Might one of these have been the name given the blade atop the brushwood mound?

In Avestan and Sanskrit, both Indo-Iranian languages closely related to Scythian, and their Zoroastrian and Vedic traditions, the spiritual manifestation of Wind is called Vayu.

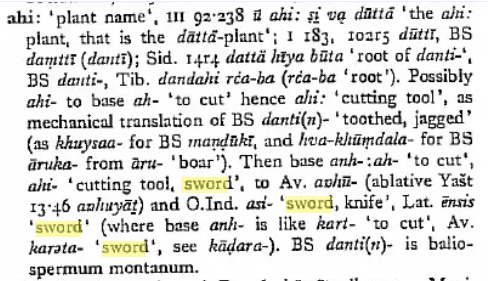

In the same tradition, spiritual manifestation of the Sword is called Asi. Asi appears in the Mahabharata as the personification of the first sword, created by Brahma in this striking literary passage:

12.161.1-87—I have heard from the Rishis that soon something very awful occurred in that sacrifice. It is heard that a creature sprang (from the sacrificial fire) scattering the flames around him, and whose splendour equalled that of the Moon himself when he rises in the firmament spangled with stars. His complexion was dark like that of the petals of the blue lotus. His teeth were keen. His stomach was lean. His stature was tall. He seemed to be irresistible and possessed of exceeding energy. Upon the appearance of that being, the earth trembled. The Ocean became agitated with high billows and awful eddies. Meteors foreboding great disasters shot through the sky. The branches of trees began to fall down. All the points of the compass became unquiet. Inauspicious winds began to blow. All creatures began to quake with fear every moment. Beholding that awful agitation of the universe and that Being sprung from the sacrificial fire, the Grandsire said these words unto the great Rishis, the gods, and the Gandharvas. This Being was thought of by me. Possessed of great energy, his name is Asi (sword or scimitar). For the protection of the world and the destruction of the enemies of the gods, I have created him. That being then, abandoning the form he had first assumed, took the shape of a sword of great splendour, highly polished, sharp-edged, risen like the all-destructive Being at the end of the Yuga. Then Brahman made over that sharp weapon to the blue-throated Rudra who has for the device on his banner the foremost of bulls, for enabling him to put down irreligion and sin. At this, the divine Rudra of immeasurable soul, praised by the great Rishis, took up that sword and assumed a different shape. Putting forth four arms, he became so tall that though standing on the earth he touched the very sun with his head. With eyes turned upwards and with every limb extended wide, he began to vomit flames of fire from his mouth. Assuming diverse complexions such as blue and white and red, wearing a black deer-skin studded with stars of gold, he bore on his forehead a third eye that resembled the sun in splendour. His two other eyes, one of which was black and the other tawny, shone very brightly.

It should be noted that Rudra is usually associated with storms—especially winds—and warriors, particularly the wilder, frenzied aspect of the warrior role. But, as the text continues, the sword becomes a metaphor for law and justice:

"At the time, of giving it unto Manu, they said, 'Thou art the lord of all men. Protect all creatures with this sword containing religion within its womb. Duly meting out chastisement unto those that have transgressed the barriers of virtue for the sake of the body or the mind, they should be protected conformably to the ordinances but never according to caprice. Some should be punished with wordy rebukes, and with fines and forfeitures. Loss of limb or death should never be inflicted for slight reasons. These punishments, consisting of wordy rebukes as their first, are regarded as so many forms of the sword. These are the shapes that the sword assumes in consequence of the transgressions of persons under the protection (of the king).

I’m aware that Asi barely resembles “Ares.” However, it’s not unprecedented for s <—> r as in the case of the Avestan word arta “Truth,” which by some strange transformation became ashi (some have put it down to scribal error….) However it happened, could the reverse have happened with the name of a deity: Asi <—> Ari? Stranger linguistic mutations have occurred. Maybe we have a few contenders for a Scythian source of “Ares.”

Sacrifice contains multitudes

“Sacrifice is, in fact, the most prominent of all Indo-European rituals, attested in a stunning variety of forms among various Indo-European groups. Offerings included human victims; domestic animals, including horses (use of which was limited to royal sacrifices), and more commonly oxen, sheep, pigs, and goats; milk products; agricultural products; and intoxicants such as mead, wine, and the pressed drink Indo-Iranians called *sauma (Skt soma-, Av ham-, OPers houma-).

Even in its most abbreviated forms, sacrifice is a rich, complex, polyphonic act, open to a variety of interpretation by practicants and analysts—the latter indigenous and foreign—alike. It has been viewed as a gift exchange, an act of communion, commensality, or other means of bridging the chasm that separates the sacred from the profane. Alternatively, attention has been called to the fact that in sacrifice killing of animals for food is made a legitimate act instead of a sinful one, and the meat obtained thereby made sanctified instead of suspect. Yet again, the social functions of sacrifice have been emphasized, for joint participation in acts of prayer, killing, butchering, and eating serves to bind the participants in a cohesive community. Each of these interpretations has a degree of validity, and they are not mutually exclusive. Within the sacrificial practices of any given culture, it is likely that one or more of them will be most prominent, while others will also be evident, although proportionately deemphasized.

Within the sacrifices of the Indo-Europeans, another aspect of sacrifice seems to have been foremost, that which has been studied most fully by Adolf Jensen, Mircea Eliade, and more recently by Cristiano Grottanelli: sacrifice as the repetition of cosmogonic action. As we shall see, each performance of sacrifice was felt to re-create the world, dispersing material substance from its microcosmic form to the macrocosm, and thus sustaining creation. In order to demonstrate this I shall consider a number of the oldest and best-attested sacrifices as conceived and practiced by the Romans, German, Greeks, Iranians, Indians, and Celts, studying their connections to the cosmogonic mythology, implicit and explicit, as well as the correspondences among them, common points that are best understood as part of a common tradition.

Lincoln makes good on his promise to provide compelling comparisons with examples from cultures across the Indo-European world. I will limit my discussion to the Indo-Iranian sphere because you’ve already indulged me this far and I don’t want to push my luck. But if anyone is interested, you can find some more detail here, or I’ll be happy to share examples from any of the cultures mentioned above. And I can’t recommend Lincoln’s books on the subject enough. They’re always thought-provoking (though take some of the introductions with a pinch of salt.)

Herodotus himself mentions the similar rituals of the kindred Persians, among whom he lived and with whose beliefs he would have been well-acquainted, including the recitation of a cosmogony in conjunction with sacrifice and the arranging of its parts. Here too, we have the preparation of the site of the sacrifice with the laying of vegetation:

§ 1.132 Now this is the manner of sacrifice for the gods aforesaid which is established among the Persians: — they make no altars neither do they kindle fire; and when they mean to sacrifice they use no libation nor music of the pipe nor chaplets nor meal for sprinkling; but when a man wishes to sacrifice to any one of the gods, he leads the animal for sacrifice to an unpolluted place and calls upon the god, having his tiara wreathed round generally with a branch of myrtle. For himself alone separately the man who sacrifices may not request good things in his prayer, but he prays that it may be well with all the Persians and with the king; for he himself also is included of course in the whole body of Persians. And when he has cut up the victim into pieces and boiled the flesh, he spreads a layer of the freshest grass and especially clover, upon which he places forthwith all the pieces of flesh; and when he has placed them in order, a Magian man stands by them and chants over them a theogony (for of this nature they say that their incantation is), seeing that without a Magian it is not lawful for them to make sacrifices. Then after waiting a short time the sacrificer carries away the flesh and uses it for whatever purpose he pleases.

Each society, of course, has its own creation myths, and the IE cultures are no different. Most are some variation on a similar theme, which is neatly expressed by the following:

“At the beginning of time—so the P-I-E cosmogony held—there were two brothers, a priest whose name was “Man” (*Manu) and a king whose name was “Twin” (*Yemo), who traveled together accompanied by an ox. For reasons that are not specified, they took it upon themselves to create the world, and toward that end the priest offered up his brother and the ox in what was to be the first ritual sacrifice. Dismembering their bodies, he used the various parts to create the material universe and human society as well, taking all three classes from the body of the first king who—as stated above—combined within himself the social totality.”

More remarkable than the myth itself is what it suggests about its creators, who put into practice a regime of sacrifice in union with its philosophical underpinnings:

“The question they seemed to pose was this: if the body of a sacrificial victim contains the potential to re-create the cosmos, how came such potential to reside in this body? … The solution is as stunning as it is simple: the victim can become the cosmos because earlier the cosmos had become the victim. Such logic may be pursued in infinite regress and progress alike, stretching out to an eternal cycle of sacrifice and creation, matter ever flowing from microcosm to macrocosm and back again.”

Lending a hand

Lincoln offers a passage from a ritual text that accompanies the Rig Veda known as the Aitareya Brãhmana (v 2.6). After setting the stage by consecrating the victims, setting a fire, strewing the ground with the barhis, and appealing to the victim’s relatives for permission, the sacrificial dismemberment begins like so:

Lay its feet down to the north. Cause its eye to go to the sun; send forth its breath to the wind; its life-force to the atmosphere; its ear to the cardinal points; it’s flesh to the earth. Thus, (the dismemberer) places this (animal) in these worlds.

If the sacrifice’s parts were meant to be distributed to the corresponding components of the cosmos, it cannot be too surprising that the anthropomorphized cosmos, in turn, was envisioned as being composed of, cognate with, and coalescing in similar parts of mankind and his world:

Song of Purusha from RV 10.90.11-14:

When they divided Purusha, how many pieces did they prepare?

What was his mouth? What are his arms, thighs, and feet called?

The priest was his mouth, the warrior was made from his arms;

His thighs were the commoner, and the servant was born from his feet.

The moon was born of his mind; of his eye, the sun was born;

From his mouth, Indra and fire; from his breath, wind was born.

From his navel there was the atmosphere; from his head, heaven was rolled together;

From his feet, the earth; from his ear, the cardinal directions.

[Thus they cause the world to be created.]”

Numerous examples from other IE cultures survive to demonstrate that this is more than a localized cult, but an ancient philosophy common to the core of early IE consciousness.

Blood sacrifice:

It’s also worth noting that, as far as we know, blood and libations were not a regular feature of any other form of Scythian sacrificial ritual. In fact, Herodotus found it unusual that Scythians strangled all their sacrifices—except those to “Ares”—with little fanfare, giving a vivid description of the common method of dispatch by garrote:

§ 4.60 They have all the same manner of sacrifice established for all their religious rites equally, and it is thus performed: — the victim stands with its fore-feet tied, and the sacrificing priest stands behind the victim, and by pulling the end of the cord he throws the beast down; and as the victim falls, he calls upon the god to whom he is sacrificing, and then at once throws a noose round its neck, and putting a small stick into it he turns it round and so strangles the animal, without either lighting a fire or making any first offering from the victim or pouring any libation over it: and when he has strangled it and flayed off the skin, he proceeds to boil it. –Herodotus, Histories

While horses found in tombs were often sacrificed differently—stunned by a piercing blow from an axe precisely at the point of humane destruction—bloodletting distinguished this sword deity, his worshippers, and their sacrifices from the others. How?

On the chopping block

There is a simplistic case to be made that lopping off hands of rivals who try to kill you has a psychological and spiritual value of negation or dominance. It allows one to symbolically assert power. Fair enough. But is it enough to build an entire cult that endures for millennia? We are told that the Alans continued these rites. The Huns who conquered their territory, though not part of this culture, understood the meaning of this divine sword image a thousand years after Herodotus gave his report. Is a symbolic show of dominance compelling enough reason to propel such a costly practice across cultures and centuries? That explanation feels lacking to me. So does the argument that they worshipped the sword is a phallic emblem. (Not to mention, the implications of the rest of the ritual change completely: Oh, mighty Phallus, here is an abundance of hands to enjoy as you see fit! Wink.)

Though the hand in Indo-European culture and myth symbolized abstract concepts like contracts, oaths, and bonds, as in the myths of Norse Tyr or Roman Mucius Scaevola (whose name always makes me think of this), who sacrificed their hands in deceiving their oaths (in ultimately noble causes), its most obvious association was with martial force. The hand was the warrior’s fist, the thing wielding weapons in service of a tribe, king, or idea.

The sources all indicate that “Ares” was an entity worshipped by tribal leadership, whose sanctuaries and altars are located in cemeteries where kurgans of warrior nobility and chiefs are located. So this is a god of the warrior class, venerated in the ancestral burial grounds of their elites to show gratitude, bolster their martial prowess, and reaffirm their authority with powerful, violent, and terrifying rites.

But it was more than that. If warriors were the arms of the people—their strength—this deity, whoever and whatever its name was, played a role in transferring the substance of sacrificed victims into the great reservoir of the cosmos where the transmuted strength of the enemy’s arms could be tapped by the victors and, ultimately, all creation. Today we might view this through a dark lens, but in a world where survival depended on ones capacity to withstand and deliver physical violence, it was the only lens.

What is sacrifice, then?

Ultimately, it’s whatever humans have needed it to be to make sense of the world, soothe their discomfort, validate their darkness, and keep their fragile communities united. In the instances above there is another, subtler element at work—a sense of responsibility and duty to the cosmos that nurtures and sustains life. With that obligation comes a sense of agency.

Let me be clear: I’m definitely not making a case for human or animal sacrifice. In an age of science and (alleged) reason, that would be loony. Religious practice rarely survives contact with reason. I only note that, comparatively, this philosophical perspective stands out as being non-transactional, unlike what we encounter in most religious systems where humans are bargaining with invisible entities: If I give you, you give me… deal? I think of the many creeds that imagine their deity like a temperamental, high-maintenance woman who can never be placated or satisfied: Uh-oh, I screwed up again! What’s it gonna take to smooth things over this time? Flowers, jewelry… entrails?

I’m also not saying that transactional aspect is completely absent from IE culture. But in the central pillar of this worldview, practitioners do not seem to be trying to bargain or buy favor. Nor are they totally helpless or at the mercy of patronizing gods. They seem to see themselves as active participants in the re-creation and maintenance of their world. They, in concert with unseen forces around them, are responsible for the vitality of their existence. They control important aspects of their fates. Here, the rites may have been bloody, but the sentiment underlying them is oddly reassuring: Humans are not helpless children subject to the whims of incomprehensible, capricious, all-powerful deities, but co-creators living in harmony with the cosmos, assuming the immense—and terrible—duty to uphold the integrity of their world.

References:

Ammianus Marcellinus. History, translated by John Carew Rolfe (1859-1943), from Ammianus Marcellinus With An English Translation, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1935-1940, Text in the public domain.

Bailey, H.W.. Dictionary of Khotan Saka, Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Gershkovich, Ya.P.; Romashko, O.V.. Scythian sanctuaries of Ares: archaeological date and Herodotus' testimonies (in English), Ukrainian Archaeology, 2013.

Herodotus. The Histories, translated by George Campbell Macaulay (1852-1915), from the 1890 Macmillan edition now in the public domain

Jordanes. The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, translated by Charles Christopher Mierow (1883-1961), 1908, a work in the public domain.

Lincoln, Bruce. Death, war, and sacrifice: studies in ideology and practice. The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Lincoln, Bruce. Myth, Cosmos, And Society. Harvard University Press, 1986.

Lucian of Samosata. The Works of Lucian of Samosata, Toxaris: A Dialogue of Friendship, translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler, The Clarendon Press, 1905, public domain.

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, published between 1883 and 1896, public domain.

Subscribe to The Problematic Pen

Journey into the world of ancient Scythian nomads—fierce warriors, mystic traditions, and power struggles—in The Steppe Saga, a historical fiction series paired with bold indie fiction and essays exploring ancient cultures, myths, and more.

You're right, it was a long one, but well worth the read. It sounds strange saying I've had an interest in sacrifices and how they were performed for a long time, but, well, I do. I have a novel waiting for me to tackle once I get my shit together. It takes place in Rome during the Claudian/Neronian age. I used Tacitus and the New Testament for working my plot out. The thing I didn't have was info on sacrifices. But that was all written before the internet. As I don't have anything more than grade 12, it took a lot of library time to find what I was looking for. And then they brought out computers you could have in your own home. Imagine how that idea excited me! I found Wikipedia was my best source for Roman sacrifices. My daughter said, "You do know the stuff on Wikipedia is written by anyone and everyone, right?" I said, "You know I'm writing fiction and it takes place 2000 years ago, right? Who cares if it's not right?" And I still hold to that. But this is insightful, because part of my story takes place in Parthia--you can't have a story about Rome and not have Parthia in it, right? I mean, Corbulo? My 'bad guy' goes to Parthia and becomes a hero, taking the name 'Parthicus' (much the same as Scipio became Africannus.) So yeah, I liked this!

Utterly fascinating. I think your theory as to the importance of the sacrificed hands makes a lot of sense--reminds me of the (alleged) Celtic tradition of drinking wine from your once-powerful enemy's skull, as a way of absorbing his martial and leadership abilities. An excellent article, all around.