That’s just, like, your opinion, man

On meeting the 100 subscriber milestone, among other stuff...

Thank you!

My thanks go out to the now more than 120 subscribers who have taken a chance on this project. When I began The Problematic Pen in earnest back in January, I did it almost as a dare to see if I had the nerve to take my writing public in an environment where I saw so many heterodox views not only spurned but punished. I consider my views fairly mainstream and moderate, though the subjects I enjoy writing about are obscure and sometimes strange. But “moderate” is not what I read on most mainstream websites lately. Only on a platform like Substack could I have felt at home publishing my fiction and essays. But I never dreamed I’d find subscribers who would be interested in reading what I wrote. I certainly never imagined there would be so many. I’m honored to have you here.

However, the number of subscribers I had, have, or will ever have, won’t affect the core of what or how I write. I don’t write this for money and don’t want to be famous. The usual drivers of success don’t move me. I write to think, to explore—it’s one of the ways I research and work through my ideas and opinions on the various topics that interest me. As such, I value the feedback from every one of you, and I look forward to engaging with comments and emails from readers. When you share opinions or suggestions, I value your insights, and they help my work evolve—I hope I can learn from those with more knowledge and experience than myself. But if need be, I can continue this project as I began it: alone. The underlying ethos, themes, and goals remain my own, and those won’t shift to satisfy a readership, garner clicks, or lure an endless stream of subscribers. I believe most readers are here because they share this independent spirit, and I hope they connect with what they read in that light.

In that spirit, I’d like to share a couple of things I’ve been thinking about as I search around Substack, observe what’s popular, listen to the advice given about what makes a successful blog (are we even allowed to use that word anymore? ;-), see other writers express their anxieties about the platform and writing generally, and think about the future of my own newsletter.

Your taste matters more than that of your critics.

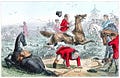

When I was about 25, I participated in a fundraising auction to support a local hunt club I was involved with. I don’t hunt animals for real, and this was more of a social club for riders that provided members an excuse to gallop around the countryside on horseback during the cooler months. No animals were harmed except the (often drunk) humans who occasionally ejected from their mounts into brambles and ditches. Yes, it’s silly, but also a tradition and lots of fun! Anyway, my contribution to the auction was the offer a horse portrait in oils. I’d seen them advertised in equestrian magazines and at horse shows for exorbitant amounts, and as a painter who had done custom portraits before, I thought allowing bidders to obtain a portrait for a reasonable amount would be nice. I quickly painted a simple sample portrait of my horse Nate, and brought it, still wet, to the event.

As several hunt members and patrons gathered around to see the painting, another artist who had set up a table further down walked over to look as well. She was an older woman—at least old enough to be my mother. One of the members there recognized her and asked what she thought. She stood in front of the painting, arms folded, and said snootily, “No. I don’t think so.” Judgement rendered, she walked away without a word to me.

I took her to mean that my painting was somehow flawed, not up to her high artistic standards. Yet, she never explained why or what might have been done to improve it. I would have welcomed that. But she simply came along to take a dump on my piece and left.

Being young, naturally shy, and lacking confidence in my skills, I didn’t defend myself. I didn’t voice the thoughts in my head—which was maybe for the best, because they mainly began with “c” and ended with “t.” But I was left wondering if the world—and other artists—could see something in my work that I was blind to. After all, I was mostly self-taught. There was a lot I probably didn’t yet know about painting. What if she was right, and my artwork was total shit?

But then my curiosity got the better of me, and I worked up the nerve to go look at her surely superior work, spread out across a whole table. It looked to me like something the average third grader might have done with some cheap brushes and no concept of perspective. Disproportionate, globular figures filled canvasses awash in a mishmash of paint textures, chaotic brushstrokes, and depthless, dead-eyed figures. It was a bad parody of impressionism if that style had been invented by chimpanzees allowed to play with children’s paint sets. I thought: Wow, her work is total shit. Who the fuck is she to judge me?

It was a classic clash of aesthetics. And it was then I learned a valuable lesson about allowing my work to be judged by those whose work I don’t respect—whose tastes or inclinations I don’t care for. These things are subjective, and people are entitled to their own preferences, but they’re not entitled to elevate their own partialities and work by attempting to degrade or discourage mine through the pseudo-authority of snobbery, condescension, insults—or worse. And the only way that can happen is if I allow it to—if I internalize and adopt their negative critiques. Taste is individual, not universal. No one is the final authority on what makes “good” art, and certainly not on whether a work of art deserves to be enjoyed by others.

Although I didn’t see the appeal, other people clearly liked her paintings, and that’s great. I hope she has a long and prosperous career. But recognizing that a negative critique is just one person’s opinion, not an empirical fact, is an essential step in becoming a better creator, consumer, and critic of art, including literature. So much of what we write is segregated by self-appointed gatekeepers who claim some divine right to determine what is and is not worthy of an audience. I see many authors who believe that being stranded on the “wrong” side of those gates must mean their writing is worthless. But they are allowing people whose values and taste they often don’t share to condemn their work rather than offering it to those who can truly appreciate it. I believe there are far more of us than there are of them, all hungry to connect with the unique, vibrant, untamed stories most publishers no longer have the balls to print. Perhaps it’s those snobs who are the ones stranded on the wrong side of the gates?

Because sometimes even the so-called experts are wrong.

Before the incident of the portrait, I was starting young horses for an importer/breeder. I fell in love with one of those horses—the one from the painting above, Nate—and bought him. Although I was training him myself, even Olympic-level riders have coaches to help them with their schooling, and still I wanted someone to help me with the finer points of Nate’s training, especially when it came to jumping bigger fences. We’re always learning, ideally.

One day I was in the Grand Prix field with this coach, and she directed me to jump the liverpool, a type of water obstacle. Nate had never jumped water before, but I rode him toward it calmly and confidently in the hopes he’d sail over it like he did with most things. He did not. He spooked and refused it.

Now, common horse training wisdom in the English-style disciplines is that you punish a horse for a refusal with spurs, crop, or both. However, since it was his first time seeing the thing, I just let him stand there and look at it. But the trainer started screaming. I explained my thinking. Unimpressed, she told me to try again. I did as instructed, and again he refused. This time she wanted me to punish him for real. I suggested that I could get off and lead him over it. I’d had this horse since he was a baby, and he trusted me. Why not show him there was nothing to fear? That’s what I’d always done, and it had always worked.

Her answer: You can’t do that at a horseshow!

But we’re not at a horseshow, I said. We’re at home, introducing a green horse to something new. What we do today will be the foundation for the rest of his career.

Not about to be contradicted, she told me to get off so she could ride him. In other words, so she could beat the crap out of him and force him over it. I don’t need anyone to do my riding for me, and I wasn’t about to flush my years of hard work and training down the toilet in ten minutes. That was when I pulled the plug on the session and on her as my coach. The next day, I took him out to the field alone, led him over the liverpool a few times, got on, and when I rode him up to it, he jumped it back and forth like he’d done it his whole life. I never had a problem with him jumping water, or anything else, again. Liverpools, running streams, whatever crossed his path.

This time, contradicting, confronting, firing someone senior, with numerous high-level awards, sponsorships, a prestigious client list, and a high-end stable—someone I had respected—seemed beyond imagination. It’s easy to challenge those we already disagree with, and those whose approval we never sought; it’s another thing entirely to tell one’s peers and field leaders—people whose respect we crave—to take their views and shove them. Who was I? Students like me didn’t question “big name” trainers. We studied them in awe and did whatever they told us. But I have never been good at blindly following orders. It’s not a rebellious thing—I despise defiance for its own sake. It’s just an instinctual aversion to doing something without a good justification. If the rationale sounds shaky, I can’t get on board.

We all know that sometimes even the so-called “experts” are wrong. Everyone is. The ideas, opinions, and advice of people we respect and look to for guidance still need to be examined dispassionately and critically. How we handle such errors defines us, as people and as artists. “Yes-men” do prosper on some level, but they never create anything worthwhile. Contrarians likewise never create, but only tear down what others have made. The road to maturity, to creativity lies somewhere between. With honest intentions, we can challenge, refine, or reject the opinions of prophets and pundits, gurus and geniuses, and the world doesn’t crumble around us—quite the opposite.

I knew what the coach had demanded of me would harm my horse and the humane training I had so carefully cultivated. It would betray the kind of horseman I wanted to be. If others were comfortable accomplishing their goals through fear and abuse, that was on them. I would do it differently or fail trying. I’ve had similar experiences with my novel when agents and others tried to convince me to cut a third of it for the arbitrary reason of “genre standards”; alter facts and terms consistent with the historical period to conform with political ideologies I don’t share; submit to the whims of sensitivity readers, etc. These would have been betrayals of the kind of writer I want to be. If other writers are ok with having their creative efforts manipulated in this way, that’s up to them. I will do it my way or fail trying.

Did the horse-showing world abandon this trainer and others like her and flock to me and my methods? Of course not. And they won’t with my novels either. I’m not so naïve to think that principled stances make even a ripple in the cynical ocean of commerce that rules the realms of horsemanship or literature. Readers, like riders, still love a winner. They crave conformity, even as they praise individualism. I accept that too. Which makes me all the more surprised and grateful for every one of my subscribers. But don’t worry, I won’t let it go to my head. I will write the same pieces today to 100 subscribers that I wrote yesterday to one. And whether tomorrow brings 1000 more or none at all, my words will remain unaffected.

Final Thoughts

Art is not a popularity contest, and neither is living an honest life. Not every person with more age, experience, followers, money, publications, sales, sponsors, or education is automatically worthy of our admiration. Indeed, some are worthy of our indifference, especially if they employ those metrics to diminish our worth. Success is often justified by hard work, experience, expertise, excellence. We should take note of that and listen when experts speak. But we should also carefully question and assess what we hear, especially when it comes to criticism and advice. In the end, we’re responsible for making our own choices, artistic or otherwise. Indeed, one of the most powerful tools we have is the capacity to disregard. Use it wisely.

An absolutely wonderful post - I enjoyed every wise word of it. Critics are not always kind, and it's really tough to be the subject of such a challenge. What an extraordinary person though, whose eyes couldn't see the beauty right in front of her and chose to say what she said to you. In your portrait Nate glows like Whistlejacket - what an amazing piece of work!

I've just been enjoying looking at the art on your website. Just wow.

Congratulations on your milestone! :D

While I was teaching one of my temporary colleagues was an artist doing supply teaching for a while. He showed me some of his favourite paintings, which were basically squiggles, and said I couldn't see the difference between them and the things I'd seen five year-olds doing. Rather than explain to me why and how these paintings were good, he just lost his temper and told me I knew nothing about art. Well, he was a teacher, at least temporarily, so why didn't he try to enlighten me?

It's because these people know, on a deep level, that it's all BS. I'm convinced of it.

Many years ago I was walking around the LA Museum of Modern Art, with my cousin who was a graphics artist and had a degree in art psychotherapy, which she practised at the time. So I was looking at the captions to these so-called artworks, and they were full of stuff like "In this painting the artist has captured the inner essence of what it means to be human, executed in a dynamic yet understated style that renders the message even more relevant."

So I said to my cousin: is this actually meaningful? I mean, have I simply not understood it.? She looked at it, walked away, and as she did so she bellowed "CRAP!". It made me feel a whole lot better!

Anyway, I like the work you've shown here, but as I said, I know nothing about art! LOL