Hey, it’s been a while! Hope everyone is enjoying their holidays. Here’s an odd little post to close out the year for me. Happy New Year! See you in 2024 :-)

For a man who has often been called “the father of lies,” Herodotus has proven surprisingly reliable, at least when it comes to his reporting on the ancient Scythians. Now, with the recent study, “Human and animal skin identified by palaeoproteomics in Scythian leather objects from Ukraine,” published in PLoS ONE, yet another unusual detail from The Histories has seemingly been reconfirmed.

According to Herodotus:

§ 4.64 That which relates to war is thus ordered with them: — When a Scythian has slain his first man, he drinks some of his blood: and of all those whom he slays in the battle he bears the heads to the king; for if he has brought a head he shares in the spoil which they have taken, but otherwise not. And he takes off the skin of the head by cutting it round about the ears and then taking hold of the scalp and shaking it off; afterwards he scrapes off the flesh with the rib of an ox, and works the skin about with his hands; and when he has thus tempered it, he keeps it as a napkin to wipe the hands upon, and hangs it from the bridle of the horse on which he himself rides, and takes pride in it; for whosoever has the greatest number of skins to wipe the hands upon, he is judged to be the bravest man. Many also make cloaks to wear of the skins stripped off, sewing them together like shepherds' cloaks of skins; and many take the skin together with the finger-nails off the right hands of their enemies when they are dead, and make them into covers for their quivers: now human skin it seems is both thick and glossy in appearance, more brilliantly white than any other skin. Many also take the skins off the whole bodies of men and stretch them on pieces of wood and carry them about on their horses.

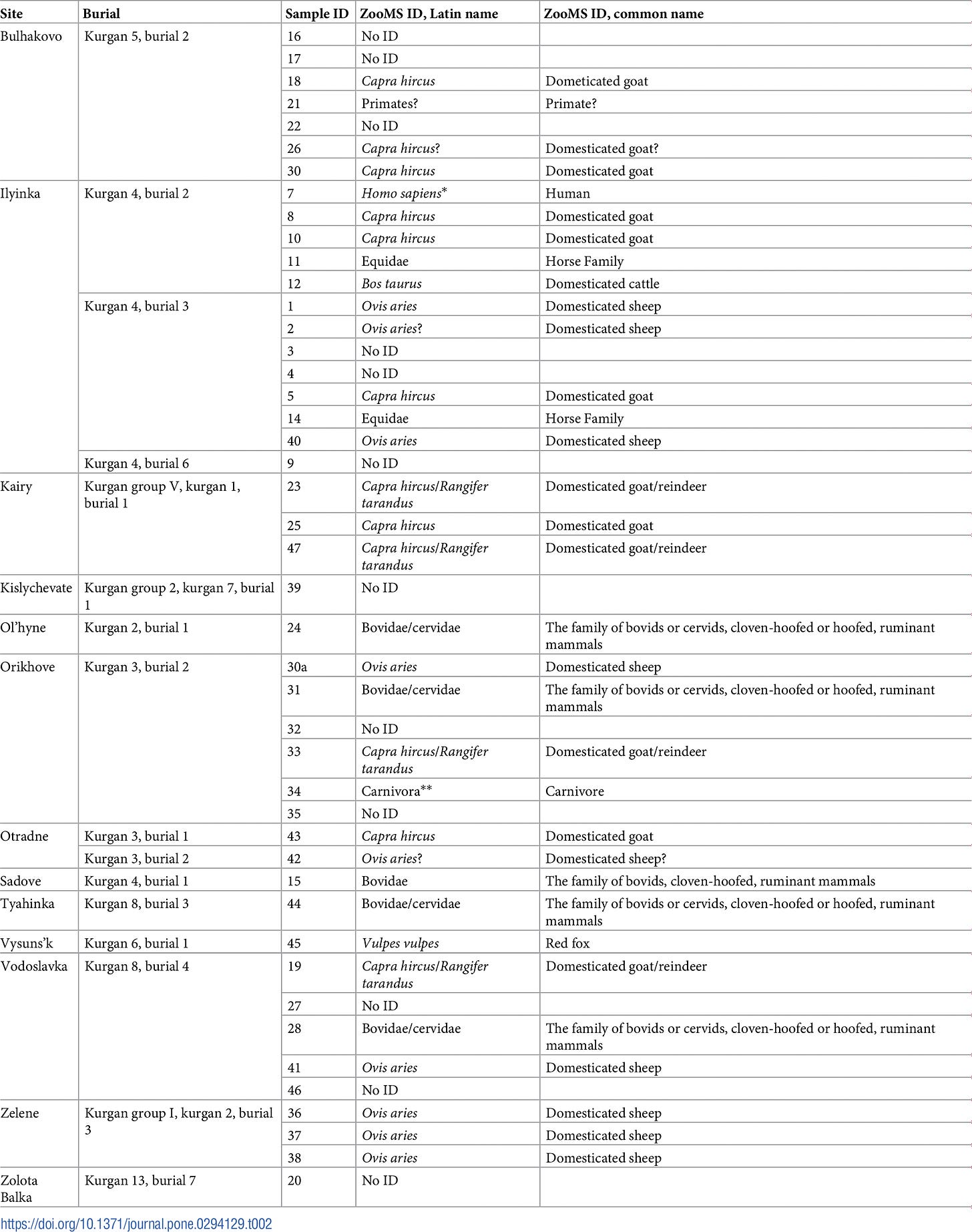

Gross! Ok, I’ll try to tackle the other traditions described in the above passage in a separate post. For now, I’ll focus on the hands. The study sampled scraps of leather found in excavations from Scythian sites in southern Ukraine and came to some interesting conclusions. Of the 45 ancient leather and fur samples taken from 18 burials at 14 different sites, only 33 could be identified. Most belong to domesticated animals like sheep, goats, horses, and cows. Sheep and goat leather represented more than half of the confirmed samples, likely valued for its availability, softness, and durability. Goat leather, in particular, is known to be water resistant, which would make it ideal for use in items like the Scythian gorytos, a combination bowcase/quiver which housed the Scythian-style composite recurve bow and arrows, both of which would need protection from the elements.

Other samples included rugged horse- and cowhide, and more exotic furs from wild animals like red fox, squirrel, and an unnamed feline species.

Oh, and two of the samples were human skin. Um, yeah.

The quiver from Bulhakovo Kurgan 5, burial 2, appears to have been mainly composed of goat leather with a tiny portion of human skin added as an accent, perhaps decoratively or, more likely, to serve in a ritual/magical capacity. Similarly, a small proportion of human leather from the Ilynka Kurgan 4, burial 3, quiver 2 example is combined with goat and cow leather. While the paper claims that the human leather appears at the “top” portion of the quivers, this is a bit misleading, as the latter quiver clearly shows “sample 7” positioned midway down its side, while the drawing for “sample 21” looks like it is located on the back rim of the quiver. For me, “top” would imply a position near the rim, while “front” would better describe the portion facing outwards. My guess is that the human leather was probably integrated into the quivers wherever its owner believed it would 1) be seen, 2) lend some amuletic power or apotropaic protection to the wearer, or 3) probably both.

Of course, there is no way to know what part of the body this skin came from, but it is intriguing to think it may have come from hands, as described so vividly by Herodotus. Why would he have specifically mentioned it otherwise?

But why skin from human hands?

This was probably weird even to Herodotus, who found it curious enough to relate to his audiences in the 5th C. BCE. It’s no less bizarre to us today. The Scythians had vast herds and access to hides from various species, including wild and domestic animals, each offering different properties and requiring specialized preparation methods. They were aware of these and skilled in their uses. With an impressive knowledge of tanning techniques and no shortage of leather types to choose from, the Scythians did not lack options to clothe themselves or cover their bow cases. Under these circumstances, “hand leather” seems wildly impractical. Further, Herodotus goes to great lengths to tell us that they specifically chose the skin of enemies’ right hands, which, if we’re being economical, will not cover much of anything. There have to be better choices out there for one’s leatherworking needs. So, why?

There must have been a logical explanation behind this deliberate choice beyond the simplistic notions of convenience or savagery. The urge to comprehend the inner workings of different cultures is a double-edged sword for those who wish to immerse themselves in the sometimes horrifying world around them. This includes the exploration of both contemporary society and the past. Examining the enigmatic customs of bygone eras and respectfully attempting to comprehend them are the aspects of (pre)history and the craft of writing historical fiction that most captivate me. This does not imply refraining from personal judgements. Instead, it means making an earnest effort to understand people, places, and eras on their own terms before rendering any judgements.

In the case of the Scythians, they seem to have had something of a fetish for right hands, especially those of their enemies, as suggested elsewhere by Herodotus:

4.62 Every year they pile on a hundred and fifty waggon-loads of brushwood, for it is constantly settling down by reason of the weather. Upon this pile of which I speak each people has an ancient iron sword set up, and this is the sacred symbol of Ares. To this sword they bring yearly offerings of cattle and of horses; and they have the following sacrifice in addition, beyond what they make to the other gods, that is to say, of all the enemies whom they take captive in war they sacrifice one man in every hundred, not in the same manner as they sacrifice cattle, but in a different manner: for they first pour wine over their heads, and after that they cut the throats of the men, so that the blood runs into a bowl; and then they carry this up to the top of the pile of brushwood and pour the blood over the sword. This, I say, they carry up; and meanwhile below by the side of the temple they are doing thus: — they cut off all the right arms of the slaughtered men with the hands and throw them up into the air, and then when they have finished offering the other victims, they go away; and the arm lies wheresoever it has chanced to fall, and the corpse apart from it.

Bruce Lincoln proposes a fascinating perspective on these rituals, suggesting that they serve as a reenactment of the ancient Indo-European sacrifice conducted by the progenitors Manu (Man) and Yemo (Twin). According to the ancient PIE cosmogony, Manu, the first priest, sacrificed his twin Yemo and used his dismembered body to shape the material universe and establish the foundations of human society.

Subsequent sacrifices mirror this original act, aiming to recreate or replenish the harmony within the cosmic order. These rituals echo the belief that the various elements of the individual’s body serve as building blocks for the material world, as well as the intricate web of human interactions and social structures. By performing these rites, individuals seek to invoke the creative power that brought the universe into existence and to reaffirm their connection to the cosmic order. Through the act of sacrifice and the subsequent distribution of the parts, they participate in and bolster the ongoing process of creation and social organization.

It’s within this context that the significance of these rituals becomes apparent. They’re not merely acts of appeasement or offerings to divine entities but rather intentional reenactments—or partial reenactments—of a primordial event. Each sacrifice carries cosmic significance, invoking the act of creation with each offering.

To exemplify this point, Lincoln quotes from a related Indo-Iranian context with the “Song of Purusha” from the Rig Veda (10.90.11-14), in which the various classes of society are envisioned as the corresponding members or organs of the cosmos from which they were created in this cosmogony:

When they divided Purusha, how many pieces did they prepare?

What was his mouth? What are his arms, thighs, and feet called?

The priest was his mouth, the warrior was made from his arms;

His thighs were the commoner, and the servant was born from his feet.

As I have written elsewhere, in this conception of the material and social order, arms/hands logically represented the warrior class and martial strength or force, so it’s unsurprising that the skin taken from the hands of enemies would be used in the quasi-magical manufacture or embellishment of warriors’ weaponry or, in this instance, a gorytos, the combination bowcase and quiver ubiquitous throughout Scythian art and culture (the symbolism of the gorytos is worth its own post someday!) This may have been understood as a creative act engendering a kind of transfer of power, imbuing one’s weaponry with this elemental martial energy.

As above, so below… or something.

Lincoln’s interpretation sheds light on the profound depth of these traditions, suggesting that they transcend mere metaphor and assume the role of transformative rituals that tie individuals to their cosmic origins and empower them in the maintenance of their world. They provided a means to engage with the cosmic forces that shape human existence and perpetuate the delicate balance of the universal order.

While unquestionably unsettling by today’s standards (as most ancient practices are), delving into the religious and philosophical perspectives underlying such practices may potentially grant us a glimpse into their underlying rationale. Consequently, the perception of human leather production as a repugnant sacrilege necessitates a more nuanced understanding. Unlike subsequent religions that propagate the idea of the physical body being an insignificant earthly vessel, imprisoning an inscrutable moral soul yearning for liberation, these ancient societies held a divergent belief. They regarded their bodies as embryonic microcosms of the wider cosmos, intrinsically interwoven with every aspect of nature and society, enabling them to tap into and harness the boundless forces of creation.

There’s an undeniable majesty in this outlook. As we explore practices from the alien past, we excavate the hidden depth in ancient rites that may, at first glance, elicit bewilderment or even revulsion. By doing so, we hopefully foster a greater appreciation for the complex ways in which ancient cultures sought to comprehend their place in the universe. Only by stepping outside our common modes of thought and delving into such unfamiliar perspectives can we broaden our understanding of the human condition. What we find might just surprise us.

Thanks to

for sharing this article with me. I also enjoyed the blurb about it in ‘s Ancient Beat, which I highly recommend if you’re an archeology nerd like me :-)References:

Brandt LØ, Mackie M, Daragan M, Collins MJ, Gleba M (2023) Human and animal skin identified by palaeoproteomics in Scythian leather objects from Ukraine. PLoS ONE 18(12): e0294129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294129

Herodotus. The Histories, translated by George Campbell Macaulay (1852-1915), from the 1890 Macmillan edition now in the public domain

Lincoln, Bruce. Death, war, and sacrifice: studies in ideology and practice. The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Lincoln, Bruce. Myth, Cosmos, and Society. Harvard University Press, 1986.

Subscribe to The Problematic Pen

Journey into the world of ancient Scythian nomads—fierce warriors, mystic traditions, and power struggles—in The Steppe Saga, a historical fiction series paired with bold indie fiction and essays exploring ancient cultures, myths, and more.

Another brilliant and captivating essay. It makes sense to me that they would use the right hand for several reasons, including many you already laid out. I’m reminded that, when the Romans said goodbye to one another, they’d often say, “Eo dextro pede,” which means “go forth on your right foot [first].” And when Roman soldiers took their first step when marching in formation, it was always on their right foot for good luck. A person’s power (virtue) was also believed to be contained in the right hand. So I wonder if they were thinking that in using the skin from the right hand they were sort of giving their quivers a “kevlar” sort of coating.

Great writeup! Thanks for the mention. 😀